Article:

BY ANITA B. STONE

This is the story of two men whose partnership during segregated times would change history forever, transforming America and leaving an impact on the lives of thousands of African American children and adults. The good work these men accomplished shaped generations, the historical remnants of which continue to exist in Wake County today.

This story begins in 1911 when Julius Rosenwald, a Chicago philanthropist and progressive who had succeeded Richard Warren Sears as president of Sears, Roebuck and Company in 1910, met Booker T. Washington, a man who had emerged from slavery to become a teacher and founder of the Tuskegee Institute in 1881 in Alabama.

While training prospective teachers in a one-room shanty that would become the Tuskegee Institute, Washington also searched for philanthropic assistance to meet the educational needs of African American children. As the institute’s president, Washington managed to raise money for what would later become one of the greatest institutions of higher education for African Americans.

Washington and Rosenwald met during a prearranged luncheon and discovered they had similar goals to educate children in the South who were receiving little or no education. Rosenwald soon became one of Washington’s benefactors, and Washington offered Rosenwald a place on the Tuskegee Institute board. Rosenwald read Washington’s “Up From Slavery” book, which sparked his interest in charitable works and, primarily, his desire to improve the lack of higher education for Black students.

With no land, buildings or teachers, Washington and Rosenwald had only state legislation authorizing schools to meet this challenge. On the occasion of Rosenwald’s 50th birthday, he presented Washington with $25,000 to aid Black colleges and preparatory academies.

Washington then asked Rosenwald if he could use a small amount of the money for elementary education. By 1912, Rosenwald and Washington had launched a pilot program and the Rosenwald Fund was created to continue and expand Rosenwald’s charitable activities. This marked the beginning of a plan that would result in building more than 5,000 schools for children across the South. The concept of the Rosenwald School was born.

Communities Unite

The first phase of creating Rosenwald schools consisted of plans for six schools in Alabama. But there was one requirement: Each community would need to donate the land and raise matching funds for erecting their school. From 1914–1916, Rosenwald funded several hundred more schools, and in 1917, the Rosenwald Fund was incorporated in Chicago with support from the Tuskegee Institute. The fund moved to Nashville, Tennessee in 1920 when it grew too large for the Tuskegee Institute to manage it.

The construction of Rosenwald schools brought communities together. They became centers of small rural settlements. Such Black communities were an important characteristic of the rural landscape in the first half of the 20th century. The idea of building schools for impoverished children uplifted many families, and Rosenwald schools completed the interlocking array of philanthropies Washington helped assemble to improve Black education.

Rallies were held to raise money and collect supplies. In many communities, hogs and chickens were raised and sold to help provide funds for school-building. Citizens donated thousands of feet of lumber cut from their own lands, hauled by their own teams to a sawmill, and then laid down on a lot purchased with their funds.

These exciting times sparked $4.7 million in contributions from Black communities. In some North Carolina counties, Black farmers won grants to build schools and local governments spent $18.1 million with private local white contributions making up any difference in construction costs. Wake County contributed more than $866,000 toward Rosenwald buildings.

Everyone came on board to work together. Rosenwald schools began to pop up across North Carolina and other parts of the South. According to NCPedia, at one time North Carolina had at least 800 Rosenwald schools—more than any other state.

A Legacy Partnership

The Rosenwald-Washington partnership became a pillar of the Civil Rights Movement and was a major contribution to ending segregation in the Jim Crow South, leaving a legacy that would reverse years of inequality in education because of slavery.

Rosenwald died in 1932 at the age of 69, but the schools he funded helped stabilize industrial and social conditions by encouraging Black people to own and build their own homes near the schools. On May 17, 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled segregation as unconstitutional, and the schools were slowly phased out. Many closed, some were torn down and others were left standing for various uses.

Having died at the young age of 59 in 1915, Washington never got to witness the full impact of his educational endeavors. Today, the Tuskegee Institute he founded is known as Tuskegee University, where more than 2,100 students are registered on the 5,000-acre campus that accommodates 150 buildings.

Washington’s legacy became an historic one. His monument, located on the Tuskegee University campus, was dedicated in 1922. The inscription reads, “He lifted the veil of ignorance from his people and pointed this way to progress through education and industry.”

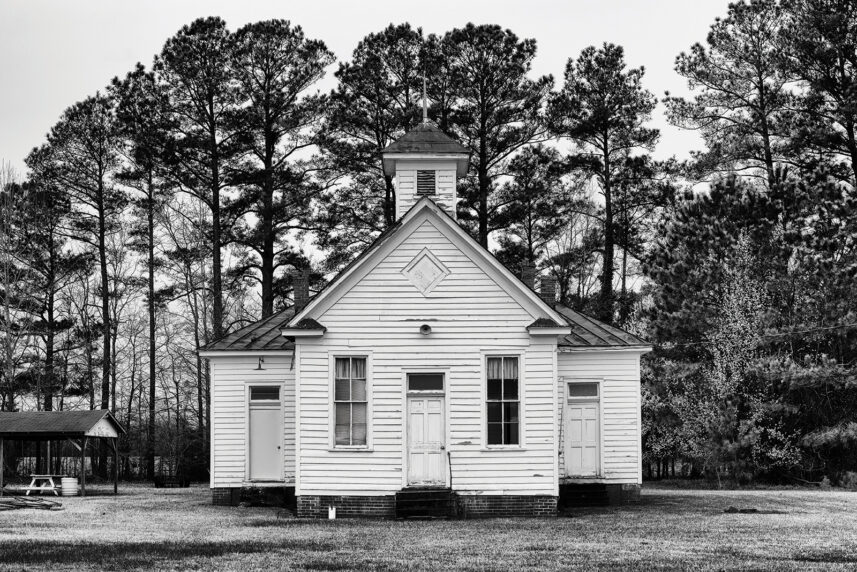

Today, the Rosenwald school buildings that still survive in Wake County stand as a testament to African Americans’ tenacious pursuit of education. Prominent leaders such as poet Maya Angelou, late Georgia congressman John Lewis and civil rights activist Medgar Wiley Evers were products of the Rosenwald era.

The October 1988 edition of the North Carolina Historical Review published these words about Rosenwald schools, written by Thomas W. Hanchett, who was a UNC–Chapel Hill doctoral student at that time: “Today the structures stand forgotten, scattered across the North Carolina countryside.

Some are houses, businesses or barns. Others, those that stand next to churches as community halls, still retain the large windows that mark them as school buildings. These are Rosenwald Fund schools, landmarks in the history of Afro-American education.”